Religion wasn’t supposed to last. Within academia and Western society, early religious scholars predicted faith would decline as science advanced and discoveries, instead of tradition, answered fundamental questions.

But even with biology, astronomy and physics providing answers to the questions once asked in churches, mosques or temples, people still flock to congregations.

“I think it means there’s a longing in our souls for something beyond science,” said the Rev. Robert Matya, chaplain of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Newman Center at St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church. “People want fulfillment for the longing in their hearts, and we believe we find that in our faith.”

But as people find fulfillment in faith, they also find incongruity. Contemporary social, political and moral understanding influence identity, interaction and how people view the world. And when looking for guidance in centuries-old texts, some become more confused than reassured.

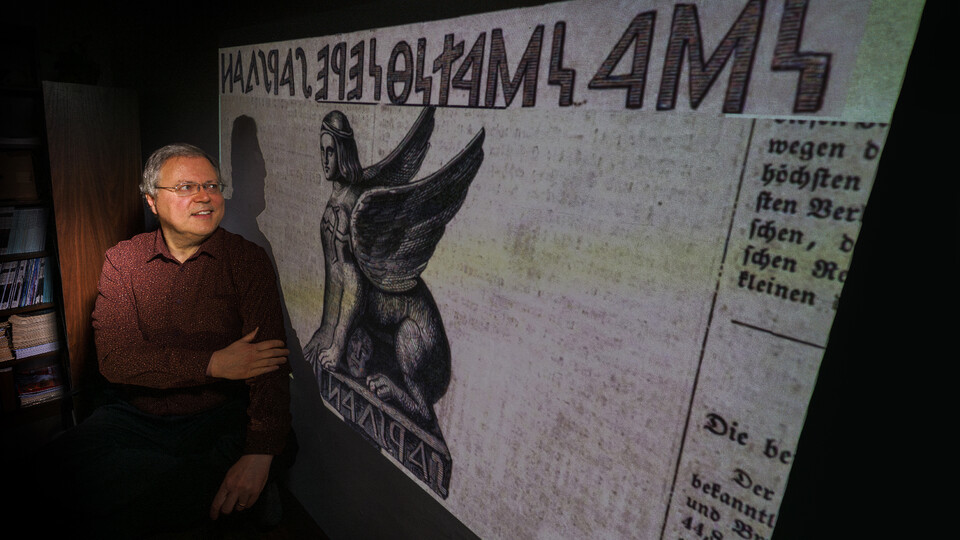

To Be Religious and Modern, a new class offered by the Department of Classics and Religious Studies, explores the dynamic between modernity and religion.

“How do we look at what a lot of people would understand as conflicting epistemologies: our religious worldview, our scientific worldview, our ‘modern worldview’?,” the class’s professor, Max Mueller, asked. “Modern means different understandings of gender, race and ethnicity than what religion had provided for. So how do people answer that?”

Mueller and his students will explore the question of religion and modernity in three nations: the United States, France and India. These three were chosen because of the different ways they view the relationship between religion and politics.

In the U.S., citizens are “practically invited to bring our religiosity into the public sphere,” while in France, it would be considered offensive to say “God bless France,” Mueller said. In India, the world’s largest republic, worship is ubiquitous but comes in a variety of disciplines.

Mueller will use text and historical artifacts to explore modern belief, people, science and violence in each of the three nations.

The latter will be explored in the context of three relatively recent events: the Boston Marathon bombing, the murder of abortion doctor George Tiller and France’s ban of wearing the burqa or burkini.

Current events evoke questions about how religion interacts with the complexities of today’s world, he said. The class will analyze how people use religion to promote political, sometimes terroristic, agendas.

“Were the young men of the Boston Marathon bombing really acting based on some kind of true Islamic belief?” Mueller asked. “Or did other reasons lead to their alienation or their failure to integrate into the American experience?”

Mueller said even in less extreme examples, there are signs of the conflict between religion and modernity.

A Pew Research Center study found Evangelical Christians were the largest demographic of supporters of Donald Trump’s previous plan to close the U.S, to all Muslims. The same study reported atheists to be the largest demographic of opponents.

“We see these non-religious folks wanting to welcome, believing America is a place where people can come to find refuge,” Mueller said. “And we have a community of religious folks who self-identify with a religion that claims that a major — if not main — tenant of their affiliate is to care for their neighbor refusing to welcome. So there is an inherent conflict.”

Religious leaders throughout Lincoln and the university community said there is conflict between faith and modernity. But they don’t think one has to be independent of the other.

“We don’t have a choice but to live in the times which we live in,” said Rabbi Craig Lewis of the South Street Temple, a Reform Judaism congregation. “People haven’t changed over time, just our willingness to accept differences and willingness to live among people different than us.”

But Lewis said religion can help bridge that gap. Religion, he said, needs to adapt as times change and not remain stuck in the time it was born into.

“Religion and politics can mix,” Lewis said. “Our understandings of national and world politics can be guided by our religion because our religion teaches important values.”

But, Lewis said, a line must be drawn when religious beliefs start imposing on others’ freedom. For instance, while Jews don’t eat pork, he’d never propose legislation prohibiting it for all people, he said. For him, the relationship between religion and modernity can inform opinions, but once one inhibits the other, freedoms are violated.

The Rev. Adam White, of The Lutheran Center at the university, said religion has a responsibility to respond to the atmosphere its followers face. White said he’s proud of how the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America has responded to modern understandings of race, gender and ethnicity. In 1970, the church accepted female pastors and in 2015, it allowed gay marriage ceremonies within the church.

White said the church took a “hard look at Scripture” to re-examine how God’s word applies to these modern issues.

“What we’re trying to do today is to figure out how a text that was written thousands of years ago in a historical context is supposed to speak for the issues we’re facing today,” White said. “And that’s a very difficult thing to do well.”

White realizes some might interpret that as bending Scripture to conform with current cultural opinions, but he hopes people see past that predisposition.

While some religious leaders see a direct need for change and adaptability, others believe their texts provide as relevant an answer to important questions today as they did centuries ago.

“There are no conflicts between politics and what I believe,” said Jawad Al-Helfi, a leader within the Lincoln Islamic community.

Al-Helfi said misconceptions about Islam can lead people to bad impressions, but the Islamic understandings of gender, race and ethnicity have never changed.

“There are no differences between gender, race and people,” Al-Helfi said. “This is the real Islam from what Allah wanted.”

Matya said that amid changing understandings of gender, race and ethnicity, the Catholic Church can seem at odds with today’s culture when it comes to issues like homosexuality and abortion. He sees some Catholics struggle with fully adopting the principles.

“It’s hard to reconcile some of those things,” Matya said. “But these are things we believe in our faith, and if we say these things are true, then they have to be things we live by.”

For some, that reconciliation can cause frustration. For others, it inspires clarity. But with those reactions and more, Mueller said the questions asked are thought-provoking and worthy of discussion. That is really what his class is all about.

“It’s not controversial,” Mueller said. “It’s provocative. It’s meant to provoke questions of our students to question their assumptions — which I would say is the point of college itself.”