Weldon Kees ’35

No one knows what, in the end, happened to Weldon Kees. His life, it turns out, is an unfinished novel; various endings have him lighting out for the southern border and beyond, hinted at in his second-to-last known conversation with anyone, while his last conversation, and his car’s last location — at the foot of the Golden Gate Bridge on the Marin Headlands side — point to a less satisfying conclusion. The Zelig of the midcentury art world, Kees popped up everywhere — seemingly all-consumed with the search for truth through art and acquaintance.

Born in 1914 in Beatrice, Weldon was the son of John and Sarah Kees, who owned an estimable manufacturing and engineering company perhaps most notable for the development of, of all things, the walking sprinkler.

After graduating from Beatrice High School, the precocious Weldon bounced around at Doane and at Missouri, from where he was drawn back to his home-state university and the unique writing program of Prof. Lowry Wimberly. Wimberly, a talented and controversial professor of English, had founded the Prairie Schooner literary anthology in 1927, and by the mid-thirties his ragged salon of creative-writing students had become legendary on campus as “Wimberly’s Boys," even though there were several notable women in their company.

Wimberly’s Boys included Jim Thompson, who would later scratch out hardbitten novels such as “The Grifters” and acquire the nickname "The Dimestore Dostoyevsky;” the folklorist Mari Sandoz, who would contribute her “Old Jules” to the American literary canon, and the anthropologist-to-be Loren Eiseley, whose “The Immense Journey” today occupies a space at the pinnacle of science-based prose.

And, it included Weldon Kees. Graduating in 1935, Kees stayed in the company of Wimberly’s Boys' emeriti for a while in the Lincoln office of the Depression-era Federal Writers Project, which Wimberly managed. Kees, as always, was restless. In 1937, he and Ann Swan were married in Denver, where he was studying library science and writing poetry on the side. New York beckoned, and finally in 1943, he and Ann moved there.

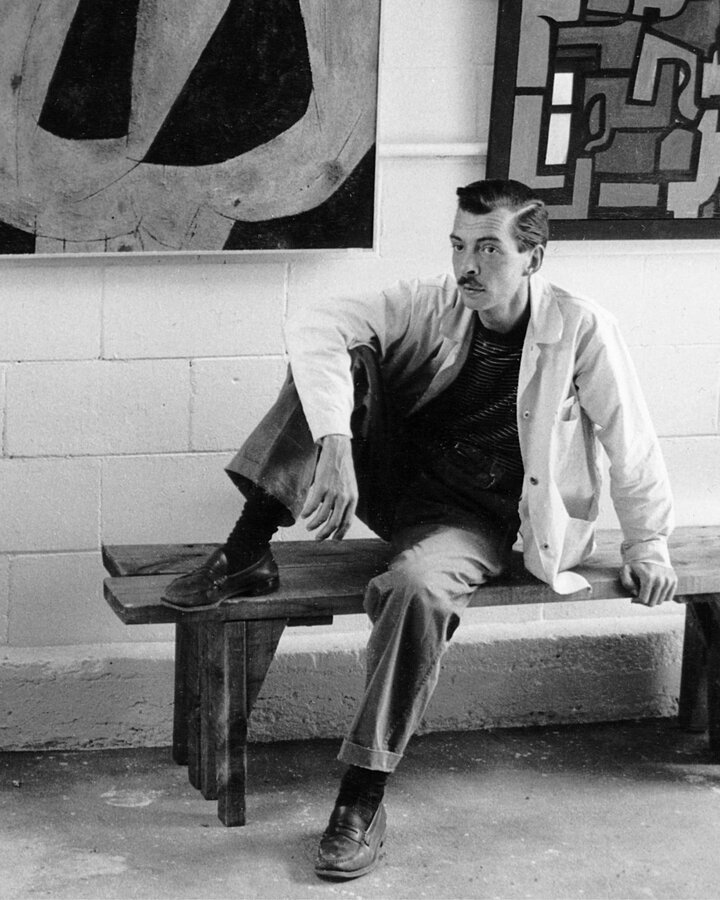

In the city, he communed with William Carlos Williams and Saul Bellow, while holding down a regular gig as a cultural critic for Time magazine. His first book of poetry, released later in the year, gained Kees entry into the pages of The New Yorker as a regular contributor of poetry. After his second volume of poetry in 1948, he shifted gears and found a spot in the Abstract Expressionist art scene with Robert Motherwell and Willem de Kooning, and in this guise produced ponderous canvases of abstract forms. By late 1950, though, he found himself estranged from New York and set out with Ann on a transcontinental drive to San Francisco.

Kees quickly found employment in a scientific research lab, the University of Californa-San Francisco’s Langley Porter Psychiatric Clinic, where he participated on a team studying nonverbal communication. In the City by the Bay, he added moviemaking to his repertoire of artistic pursuits, and cemented a friendship with Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the artist whose City Lights bookstore would become a cultural icon. In 1955, Kees and Ferlinghetti would produce an art event, “Poet’s Follies,” at which Kees was appropriately introduced as “Mr. Weldon Kees, poet, painter, artist, etcetera, composer, critic, etcetera, etcetera, ad infinitum.” Shortly thereafter, the story of Weldon Kees would come to its enigmatic end.

Today, Kees echoes in cultural history as if his life was an unfinished novel. Fittingly, he never finished his own novel, titled "Slow Parade," and like his departure, no record of it exists. Still, interest remains in his work. He has been teh subject of a full-length biography, his poetry has been collected and anthologized, and his story pops up in cultural writing infrequently, but with stubborn insistence on his significance

In 2023, a collection of Kees materials was donated to University Libraries’ Archives and Special Collections; it includes manuscripts, diaries, audio recordings, radio scripts and letters. Weldon Kees would no doubt be pleased that scholars at the university where he found his artistic footing will be wrestling with his legacy long into the future.

Weldon Kees' Slow Parade

- Weldon Kees, Papers

- The Disappearing Poet (essay by Anthony Lane in the June 26, 2005 New Yorker)

- Not Without Violence: The Disappearing World of Weldon Kees (2015 essay in The London Magazine)

- Weldon Kees (Poetry Foundation bio)

- Vanished Act: The Life and Art of Weldon Kees (Nebraska Press catalog entry)