The Center for Great Plains Studies is celebrating all the reasons we heart the Great Plains. We'll tap our Fellows, who work closely with Plains topics, our Great Plains Graduate Fellows, who are building their careers studying the region, and you! Tell us why you heart the Great Plains on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram and tag it #IHeartTheGreatPlains — we may feature your story.

Why does the Center Heart the Great Plains?

Because the Great Plains is unlike any other place on Earth. It’s a place where you can see the horizon and feel the vastness that so many before must have felt looking out on the grasslands. It’s a place where people are tied to the land – economically, culturally, historically. And it's a place of environmental priority, hosting a range of endangered species and habitats. Join with us this year, and make a case for why the Great Plains is important – and loveable.

Tell us at the Museum!

Visit the Great Plains Art Museum's lower level and use the magnetic words to tell us why you heart the Great Plains. Make sure to take a picture and tag it with #IHeartTheGreatPlains

I Heart: Six-Man Football

By Andrew Husa, Great Plains Graduate Fellow, Geography, UNL

As a result of the widespread sparse rural population of the Great Plains and subsequent low enrollments, six-man football has flourished in several of the region’s high schools. Invented in 1934 by Stephen Epler of Chester, Nebraska, six-man football has long been an excellent alternative for schools that do not have eleven boys to field the minimum number of players for a traditional football team.

Along with having five fewer players and playing on an eighty-yard field, six-man football also has a unique scoring system: field goals count for four points, and after a touchdown, the team team scores one point if it “converts” by passing or running successfully, or two points if it chooses to convert by kicking the ball through the uprights. Another rule distinctive to six-man football is that the offense must gain fifteen yards to advance through four downs compared to ten in eleven-man football. Perhaps the most exciting rule of six-man football, however, is that all players are eligible to catch a forward pass. With fewer people, more open field, and everybody an eligible receiver, six-man games are generally action-packed, so much so that newcomers to the game coming from eleven-man often observe that they look a little like a track meet.

The number of high schools playing six-man football continues to grow across the Great Plains in connection with ongoing rural depopulation across the region. While numbers are still far from the game’s peak in the early 1950s, a growing number of teams in Texas, Nebraska, and eastern Colorado, and a reintroduction of the game in Kansas and South Dakota in recent years, show that six-man football has once again become a popular solution to problems associated with shrinking enrollments.

"I Love the Great Plains"

By Wynne Summers, Great Plains Affiliate Fellow, Assistant Professor of English, Southern Utah University

When I was eight, my mother and I ran for the cellar because of a twister headed in our direction. It was July, the kind of steaming hot July in Lincoln when the cornstalks rattle together, as if they are expiring from heat and animals huddle under shade trees to escape the incessant humidity. I loved it. I could almost sense the immanent twister, the uncanny stillness that preceded the blackness and then the funnel, the way the wind stopped, then cascaded, taking fence posts and roof tops with it. The calm afterwards seemed like a slap in the face. I wanted more of those incredible storms.

I remember how my mother wrapped her arms around me in the cellar, how we both listened to the outside howl, then the silence. She often said, “I’m not sure why we live here but here we are.”

Why were we here?

My father, a medical doctor in the Lincoln University Place community, established his practice in a rectangular brick building opposite the Methodist Church. There was a dentist on one side and dad’s medical facilities on the other. I remember that building and how it expressed so much of the care-taking that went on in that small community in Nebraska and how he would get up in the dead of night, storms often howling, to deliver babies.

Nebraska storms.

They are a part of the vastness that is Nebraska, that is the Great Plains. They can terrify, charm, drain, and frighten but they are never boring. Before such storms, a human life appears fragile and inconsistent—part of something larger, something bigger, something unpredictable.

The Great Plains creates mystery. The land spreads in all directions, unmarked by mountainous vistas but no less charming or magnificent. Fields of corn and soybeans move together like a green ocean and when the summer storms come, they bend or break but endure. The crops still come in, despite twisters or thunderstorms, or huge bolts of lightning that break the night sky in two, then weave the fabric of it together again.

I have left the plains but in my mind, I will remain like that small eight-year old girl, huddled in the corner of the cellar, waiting for the power that is nature to create its spell and taunt me, humor me, and call me out again to see the way the rain looks and the thunder cracks across that wide landscape to the edges of the horizon and back again. I am part of those storms and part of all that is, at that moment.

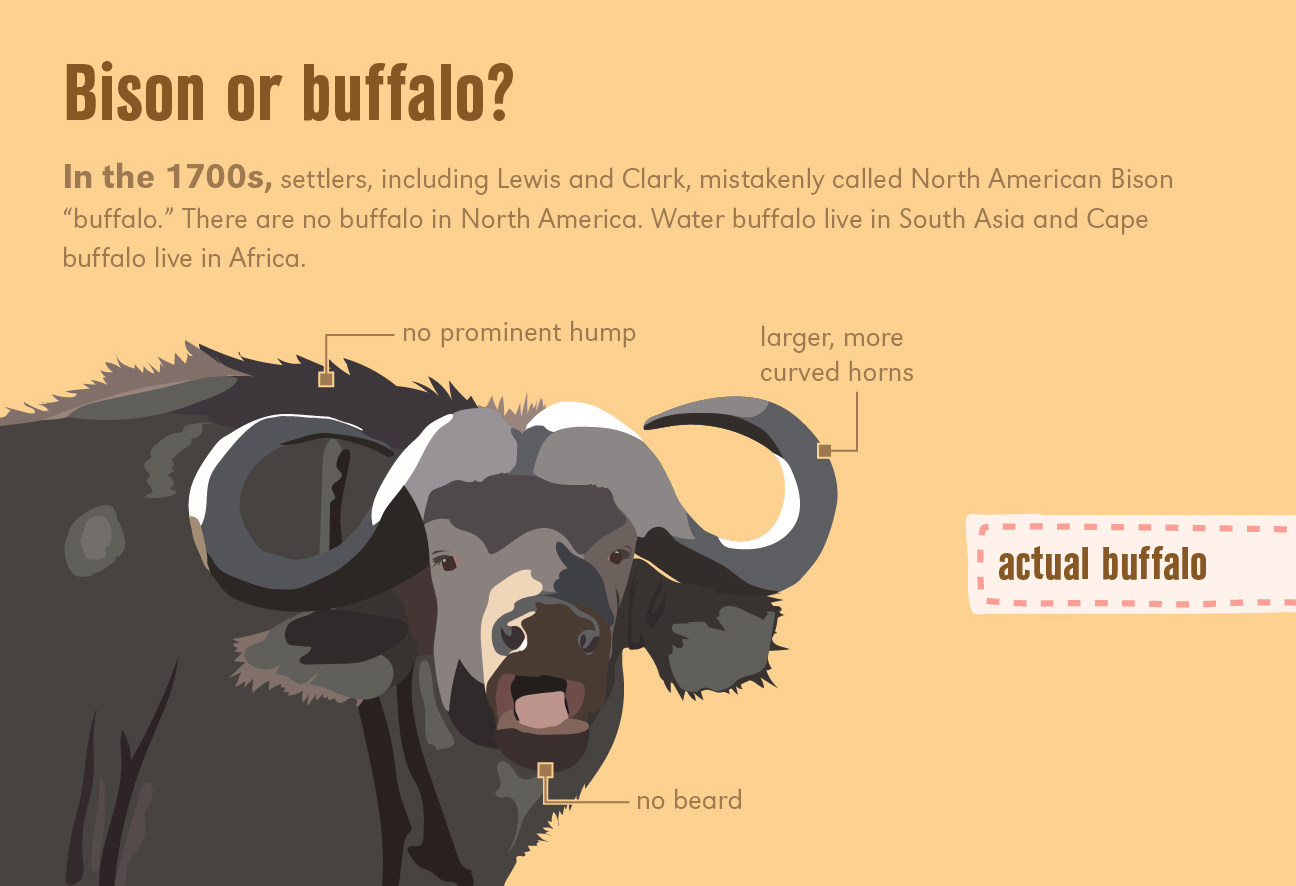

I Heart: Bison

This iconic Great Plains animal has a facsinating history that, with its recent elevation to the U.S.'s National Mammal, is still being written today. Learn more about bison from this infographic, created by Center intern Alexa Horn. Pick up a copy of the new book in the Discover the Great Plains series: Great Plains Bison by Dan O'Brien.

U.S. 83 - Why I heart the Great Plains

Harl Dalstrom, History Professor Emeritus and Great Plains Fellow, UNO

I'm a 100th meridian guy and love the vast openness - especially the feeling one gets when the fences and telephones disappear and the flashes of lighting are truly awesome.

My basic test as to whether or not one enjoys the Great Plains is how you feel about the drive on U.S. 83 from Vivian to Fort Pierre!

I'll always remember my first ride through the Sandhills and subsequent grasp of the seemingly contradictory idea of a well-watered semi-arid place.

The Black Hills, the Bessey National Forest, places like Harding County, SD, and teh vast extent of international dimensions of the region are among the points and images that come into mind!

The Great Plains

By Janet G. Smith

A place of peace to create, grow, and renew.

Surrounded by nature's sounds, sights, color and space.

Where the universe is not hidden by the city lights.

The Great Plains

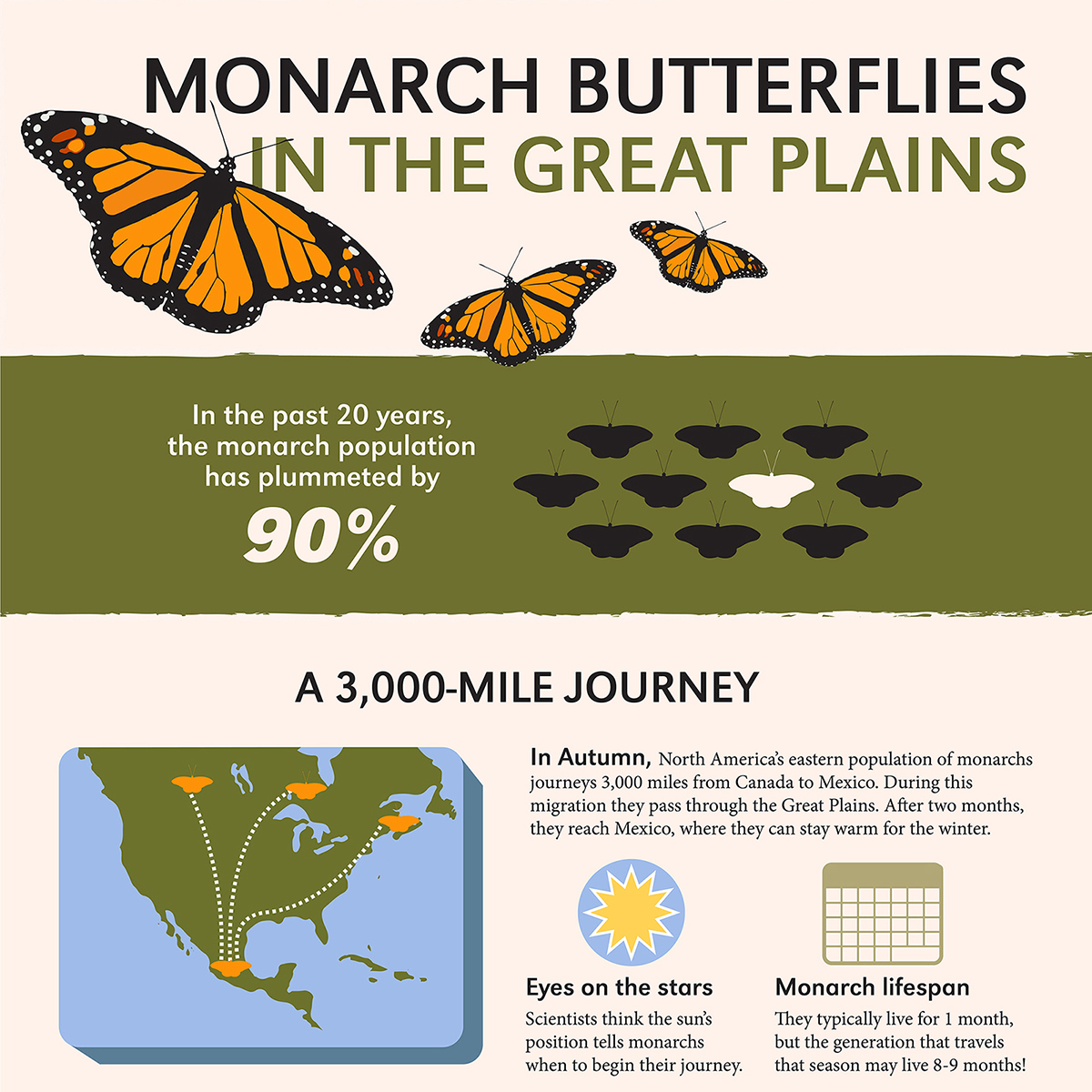

I Heart: Monarch Butterflies

Why are monarch butterflies important to the Great Plains? How do they make their epic migration? Learn more about monarchs from this infographic, created by Center intern Alexa Horn.

I Heart: The Sandhills

David Loope, Great Plains Fellow and Professor and Schultz Chair in Stratigraphy in the department of Earth & Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Nebraska, explains why he loves the Great Plains. Video by Josiah Johnson.

Driving Hate from a Great Plains Community

F. Gregory Hayden, Ph.D., Economics Professor and Great Plains Fellow, UNL

One afternoon in 1923, Greg Hayden and his son Vincent (age 14) entered a grove of cottonwoods next to a dry creek after a six mile horseback ride. They rested, loaded their rifles, and awaited the right time for the intrepid action planned. With darkness, they could see the light from the Ku Klux Klan’s burning cross in the sandy creek bed. They rode to the creek bank and started shooting into the base of the fire. As the Klansmen ran, the Haydens called out their names. They were men of the community, so the Haydens could identify them even under the sheets and hoods, by their build, by their boots, or, as Vincent yelled, “Emmett Watkins (nrn), I know that’s you under that sheet! I would know that squat anyplace.” That was the last time the Klan met in Meade County, Kansas.

I Heart: Adventure Great Plains

How Mountain Biking the Great Plains taught me to love the region’s history, its landscapes, and its peoples.By David Vail, Assistant Professor of History, University of Nebraska Kearney

I love the Great Plains, although I’m not originally from here. I grew up in Southern Oregon’s Rogue Valley where outdoor learning and adventures were part of everyday life. Mountain biking connected my passion for the outdoors and exercise, but it also taught me about interconnectedness. Relationships between wildlife, landscapes, development, and local communities all came into view as I rode the trails. I learned at an early age about the challenges, tensions, and benefits of using landscapes.

As I followed my passions for environmental and agricultural history to the grasslands, first to Kansas State University for my doctorate work and then, to UNK, I found a new joy in teaching, researching, and traversing the grasslands. Kansas’ Flint Hills offered a wealth of trails, beautiful vistas, and bison. Although challenged in elevation, riding paved and gravel roads and dirt trails placed me in the middle of Great Plains life: wind-whipped grasses; scurries of red squirrels; hunting bobcats; occasional red fox; distant humming of agricultural airplanes spraying fields of wheat or corn.

Riding the Great Plains also allowed me to have a more direct relationship with noxious weeds and pests. But poison ivy and lone-star ticks didn’t stop me. Then, at the end of a mountain biking day, the sunsets. To stop and see the sky and land meet in a beautiful array of colors renews my passion for the land even while I’m weary from the ride.

My recent move to my dream job of teaching history at UNK has also led to new dreams about the beauty of Nebraska’s environment, agricultural landscape, and local communities. I am excited to ride Kearney and adventure beyond to other Nebraska places.

Hope to see you out here.

Why Do I love the Great Plains?

P. Stephen Baenziger, Professor and Nebraska Wheat Growers Presidential Chair, Department of Agronomy and Horticulture

I love the subtlety of the Great Plains. It is easy for some to love the mountains for their grandness or the oceans for their vastness, but when you remove their size, what is really left? They are great to visit and perhaps to live if you have everything important brought to you. It does not grow there. As for the Plains with their fertile soils, you have the breadbasket of the world and a sky taller than any mountain and wider than any ocean. Underneath that sky, it is the small things that really matter. The rustle of the prairie, the surprise bloom in an arid land, the hidden animals, and the paths that led the pioneers to their destinations. Their wagon ruts still survive over a century later. It is the subtlety of the land that stirs my memories and my life.

I Heart: Plant-insect relations

The Great Plains is home to a very special plant-insect relationship between yucca plants and yucca moths. These moths pollinate yucca flowers and lay eggs in them, and the moth's larvae feed on the produced seeds. The plant cannot produce fruits without the moth, and the moth's larvae cannot survive without the seeds of the plant. This high specialized and rare relationship is called a nursery pollination mutualism and it's is one reason PhD student Shivani Jadeja hearts the Great Plains. Jadeja studies yucca-yucca moth nursery pollination mutualism at Cedar Point Biological Station, Neb. As part of her field work, she collected videos of the moths at night under IR light.

“Why I Love the Great Plains”

Dr. Matthew Bokovoy, Senior Acquisitions Editor, University of Nebraska Press

The intensity of the landscape, weather, and moods of the Great Plains immediately cast its spell upon on me when I moved to Kearney, Nebraska in August 1999 to work at UNK. Since that time, I’ve spent sixteen of the last eighteen years on the Great Plains from Central and Northern Oklahoma to Eastern Nebraska. The Great Plains receives the volatile weather that sweeps down from the Artic and front-range of the Rocky Mountains to irrigate a broad agricultural region with vast international connections. When I travel down through the Kansas Flint Hills to Northern Oklahoma, I feel like I’m upon a vast land ocean that reminds me of southern France and the Pacific Ocean of my youth. The Great Plains was not susceptible to the levels of foreign investment and gentrification in real estate experienced in East and West Coast metropolises, thus making it a great place to ride out economic neoliberalism and plan for retirement. Great Plains cities are low key and manageable, reminding me of the mellow vibes of 1970s San Diego, where I grew up.

Birding Wonders

"As a Great Plains Fellow, Associate Professor in English and Native American Studies at UNL—and lifelong birder—I love the Great Plains, above all, for its avifauna, of course!"

— Thomas Gannon, Associate Professor of English at UNL

Right: Bald Eagle at Holmes Lake, Lincoln, Neb., / Jan. 6, 2017. Bald eagles are normally seen in the Great Plains during winter months.

20 Things

"I am a New Yorker. Since moving out here, I’ve become acutely aware of the flyover bias that people sometimes have of this area. During my time here, I quickly found many things that I love about the Great Plains (and Nebraska specifically)."

— Louise Lynch, Great Plains Graduate Fellow, Entomology, UNL